An enticing prelude

For me, The World’s Best Audio System 2012 began when I met Howard Gladstone, president and CEO of Plitron Manufacturing, parent company of Torus Power, who was responsible for supplying power-conditioning equipment for the megasystem. We became instant friends, exchanging pleasantries as we traveled for 20 minutes in the courtesy shuttle from ILM airport to the Holiday Inn in Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina.

Later that evening, Doug Schneider and Jeff Fritz, respectively the publisher and editor in chief of the SoundStage! Network, hosted a gourmet feast at the Port Land Grille. The Grille’s motto, “serving Wilmington’s finest night after night,” was most appropriate for commemorating the memorable occasion. There I met the other manufacturers and reviewers who were to become an integral part of this edition of TWBAS. Venue and menu aside, the only difference from TWBAS 2009 was the fact that we weren’t asked to formally introduce ourselves. It occurred to me that 2012 was a more global gathering than 2009 had been, with audio representatives from North America, the Cahttps://www.toruspower.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/201206_simeon_300wtwbas.jpgribbean, Europe, and the Far East. This seemed to augur well for the future of high-end audio.

Later that evening, Doug Schneider and Jeff Fritz, respectively the publisher and editor in chief of the SoundStage! Network, hosted a gourmet feast at the Port Land Grille. The Grille’s motto, “serving Wilmington’s finest night after night,” was most appropriate for commemorating the memorable occasion. There I met the other manufacturers and reviewers who were to become an integral part of this edition of TWBAS. Venue and menu aside, the only difference from TWBAS 2009 was the fact that we weren’t asked to formally introduce ourselves. It occurred to me that 2012 was a more global gathering than 2009 had been, with audio representatives from North America, the Cahttps://www.toruspower.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/201206_simeon_300wtwbas.jpgribbean, Europe, and the Far East. This seemed to augur well for the future of high-end audio.

Unlike in 2009, when many of us made a beeline for Jeff’s house after dinner, we all went back to the hotel. Gladstone and I retreated to the bar for the inevitable nightcap, while listening to a live performance by a local band. The next morning, at 10 a.m., all converged on the Music Vault.

The beast and the beauty

Jeff introduced TWBAS 2012 by demonstrating to us, in groups of four attendees, short excerpts of a wide range of music. I didn’t pay much attention — my eyes and thoughts were riveted to the Magico Q7 loudspeakers, which dominated the room in more than one way.

I reflected on the Q7’s technological advances over the old Bozak infinite-baffle reference speakers that engineer and entrepreneur Emory Cook had shared with Lionel Seemungal, Henry de Freitas, and Trinidad’s small population of audiophiles in the early 1960s. In 1984 I’d even built a pair myself, to evaluate and critique recordings of steelpan orchestras of 100 to 150 players. Those massive enclosures, each 4’ square and 2’ deep, constructed from two sandwiched layers of 1″-thick marine plywood, were more akin to prehistoric monsters than loudspeakers. The sheets were glued and screwed together, with substantial reinforcement from a plethora of complex internal braces. Seemungal, who was an attorney and a mathematician, was able to write a detailed description of how to build the speakers’ low-frequency energizers, each of which weighed half a ton and housed four B-199 woofers designed by Rudy Bozak. The woofers’ variable-density cones were usually made by Bozak’s mother from a brew of paper and lambs’ wool. The tweeters and midrange drivers were arrayed in much smaller outboard quarters atop the bass cabinet, alongside a 6dB/octave three-way passive crossover.

Seemungal once told me that, at a Port of Spain trade fair, driving the Bozaks with a pair of 50W Marantz tube amplifiers, Cook had reproduced a recording of a whistle blast from the Cunard luxury liner Queen Mary. The sound, which traveled for miles, was so realistic that it remained a talking point for the local community for a long time thereafter. Cook also treated patrons to recordings of earthquakes, volcanoes, ocean waves buffeting a coast, and jet aircraft taking to the sky — as well as some music. Seemungal reiterated that “in order to faithfully reproduce the last octave without compromise, you need an infinite-baffle array that, of necessity, has to be huge, heavy, stiff, properly damped, amplifier-friendly, and ugly.”

Seemungal once told me that, at a Port of Spain trade fair, driving the Bozaks with a pair of 50W Marantz tube amplifiers, Cook had reproduced a recording of a whistle blast from the Cunard luxury liner Queen Mary. The sound, which traveled for miles, was so realistic that it remained a talking point for the local community for a long time thereafter. Cook also treated patrons to recordings of earthquakes, volcanoes, ocean waves buffeting a coast, and jet aircraft taking to the sky — as well as some music. Seemungal reiterated that “in order to faithfully reproduce the last octave without compromise, you need an infinite-baffle array that, of necessity, has to be huge, heavy, stiff, properly damped, amplifier-friendly, and ugly.”

Yet here I was, five decades after Cook’s revelation, beholding a speaker system with twin woofers housed in far narrower cabinets made of aluminum, stainless steel, and copper. Cutaway illustrations of the Magico Q7’s construction reveal the use of constrained-layer damping as well as extensive vertical and lateral bracing. The interior of a Q7 is not unlike the infrastructure of a modern aircraft carrier, and radically different from that of any conventional loudspeaker that I could recall.

The Magico is vastly superior to the Bozak in every conceivable aspect, and is far more physically attractive, despite the absence of grilles. The Q7 is a masterpiece of engineering, craftsmanship, acoustics, and ergonomics. Its evolution is mainly attributable to the combined efforts and painstaking research of Magico’s chief technical officer, Yair Tammam, and its president, Alon Wolf. The use of computer-aided design (CAD) and algorithms developed in-house to optimize the cabinet, driver, and crossover parameters has ensured seamless performance over the full audioband.

Rare-earth materials such as neodymium, as opposed to alnico V, are used for the Q7’s superpowerful driver magnets. Stiff yet light woofer cones guarantee superb transient response. As we chatted during the course of the day, Wolf told me that one of his woofers once “got caught on a metal table, and the magnetic attraction was so strong that we were unable to slide or lift it. Eventually we had to cut the table.”

The Q7s so consumed my attention that I almost took the rest of the system for granted. But how could one be nonchalant about a pair of Vitus Audio MP-M201 super monoblocks with matching MP-L201 preamplifier? The ease with which they controlled the unnoticeable excursions of the Q7s’ woofers was matched only by the enormous, palpable soundstage that was effortlessly presented as a sonic hologram behind the plane described by the speakers’ front baffles.

This was only the second time in my life that I had experienced the phenomenon of loudspeakers seeming to completely “disappear” as the actual sources of the sound. Of course, the WideaLab and Esoteric source components, Torus Power Transformers, AudioQuest speaker cables and interconnects, as well as the Silent Running Audio component rack, must also have contributed significantly to the overall naturalness of that enormous soundstage, which seemed without boundaries. But for me, TWBAS 2012 was all about the Magico Q7s.

A tantalizing interlude

With the mix of pleasant conversation, frequent samples of Andrea Fritz’s culinary skills, and an eclectic range of music played on the Esoteric combo of P-02 SACD/CD transport and D-02 D/A converter, or on the WideaLab Aurender S-10 music server, I was gradually and gently subsumed into the realism and excitement of TWBAS 2012. The listening refreshingly culminated in breathtaking performances of two popular classical works.

The first was Wagner’s Tannhäuser Overture (Paris Version), with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic — an excerpt from an original EMI Masterpiece Collection CD, remastered in DSD and produced by Motoaki Ohmachi. Tim Crable, director of sales for Esoteric, later told me that Ohmachi is Esoteric’s founder and “golden ears.” He has since retired, but still remasters recordings as a hobby. His remasterings are pressed in editions limited to 1500 copies.

As an ardent fan of Wagner’s complex orchestral music, I could feel some awkwardly large goose bumps rising on my forearms as the overture unfolded in all its majesty. I was almost moved to tears — I had never heard this spiritually uplifting composition conducted by Karajan on any label other than Deutsche Grammophon.

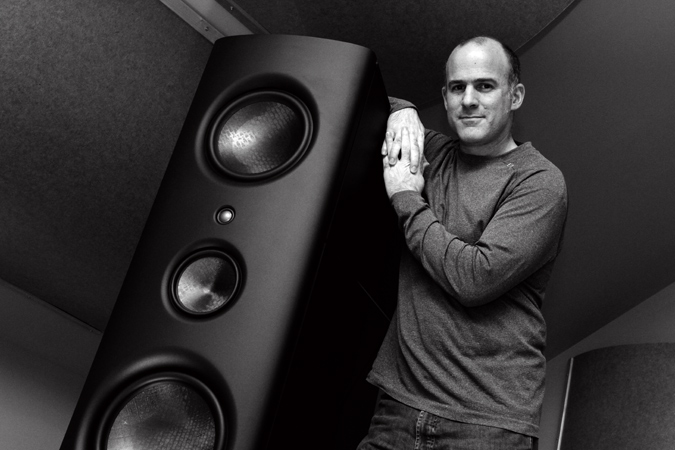

Alon Wolf with the Q7

I was even more intrigued when Alon Wolf (shown above) came upstairs with a portable SPL meter that registered instantaneous peaks of 100dB at the back of the Music Vault. No one seemed even remotely aware of how loudly the music was being reproduced.

After that mouth-watering aperitif, it seemed logical to request a correspondingly appropriate digestif. I asked Crable, who was manning the console, to regale us with Britten’s The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra. This is the first track of Britten’s Orchestra, with the Kansas City Symphony conducted by Michael Stern, produced by David Frost (SACD/CD, Reference RR120). It won the 2011 Grammy for Best Surround Sound.

I had deliberately refrained from preparing a repertoire similar to my Jurassic Lunch on Good Friday sampler, with which I’d appraised TWBAS 2009. However, Jeff had asked us to walk with a few SACDs, and I’d packed this one almost as an afterthought. Crable inserted it in the Esoteric P-02, then stood next to me, against the back wall of the Music Vault, to listen.

There were seven of us in the room at the time. The others sat comfortably at or symmetrically to either side of the sweet spot. For the 17 minutes and nine seconds of the work, no one moved, fidgeted, coughed, or was otherwise distracted. We all became part of an exotic experience: recording engineer Prof. Keith de Osma Johnson’s perfect facsimile of what had transpired in the Community of Christ Auditorium, in Independence, Missouri, on June 5 and 6, 2009. What transpired was probably the best demonstration of the seating arrangements of the four families of instruments of a full symphony orchestra that I have experienced in more than 50 years of dedicated listening.

When Crable whispered, “Simeon, don’t you think that this recording is biased toward the left side of the soundstage?,” I quickly replied, “Tim, emphasis is now being placed on those instruments in the orchestra that are located precisely there.” Then came the fugue on the main theme, in which all four orchestral voices bellow in unison in the tumultuous climax. Jeff’s Music Vault shuddered, and Crable instantly became, once again, a happy, satisfied audiophile.

At the end, I calmly said, “So, folks, now you know why Sandiford has never won a Grammy!” Hans-Ole Vitus gently squeezed the hand of his charming wife, Brita. Charles Kim, marketing-team leader of WideaLab, scratched his head, muttering to himself in Korean. Howard Gladstone and Jeffrey W. Fritz sat motionless, grinning from ear to ear. In the ensuing conversation, words and phrases such as razor-sharp delineation, image specificity, palpability, realism, depth, visceral impact, transparency, cohesiveness, intertransient silence, and black background were instantly uttered.

It all set me to thinking. I ventured outside, to the banks of the Intracoastal Waterway, for a few moments of quiet introspection that would tax my graying gray matter.

I had come to TWBAS 2012 with an open mind, knowing full well what to expect from Jeff’s costly, cozy listening environment — a manmade acoustic space that had undergone major upgrades over the past three years. If I were to write a feature story about this event, I suspected that it would have to be based on a perspective totally different from the one with which I had commemorated TWBAS 2009. Months before, Jeff had told me that the Music Vault had been optimized to the extent that “All the 2009 bugs have been eradicated.”

And that was what I had heard in all the nuance-filled recordings of music presented that day: perfect symmetry of spread from left to right, and of layering from front to back. Tim Crable apart, during that entire day no one had asked for any adjustments to be made to the balance control of the Vitus preamplifier, or questioned any aspect of the system’s soundstaging.

The inevitable aftermath

After a few sumptuous helpings of Andrea’s lasagna, homemade bread, and strawberry-topped sponge cake with whipped cream, we bade TWBAS 2012 a fond farewell and returned to the hotel. Gladstone and I were chauffeured by Crable, who had rented a spacious Honda CRV but could not join us for a final nightcap — he had to prepare for an early flight back to California.

Gladstone and I proceeded to the bar, but I immediately sensed that something was wrong. The same group was performing, but now the music sounded homogenous and irritating. Gladstone concurred, and suggested that our hearing had been thoroughly cleansed by TWBAS 2012. Perhaps we had been exposed to some form of aural baptism.

We decided to relax and enjoy our drinks on the balcony just outside the bar, to the accompaniment of Mother Nature’s timeless acoustic rhythms. As we sipped our drinks and discussed the outcomes of The World’s Best Audio System 2012, a gentle zephyr beckoned; and the Atlantic, with military precision, beat its tireless tattoo on the golden-white sands of Wrightsville Beach.

. . . Simeon Louis Sandiford